A lens on machine learning for the general public

Computer Science · · 8 min readWhat is machine learning? Why is it so hot right now? What makes a good machine learning algorithm? And what are the ethical consequences of machine learning?

What is machine learning?

Say we are programming a computer to play Super Mario Bros. How would we tell it to complete the game? Here’s one way: Run to the right, when see Goomba jump, when hit wall jump, when see question block jump. It’s very tedious. Instead, machine learning attempts to give the computer the ability to learn like a human.

What makes it easy to learn for a human? Humans learn from trial and error. Death after death, we can learn how to maneuver around obstacles, what is dangerous and what it not. Humans learn from observation. We can watch our siblings, friends, and streamer play the game and learn from their demonstrations. Finally, humans learn from habit. There’s some part of our brain from genetics and past experience that tells us it’s good to collect coins and not run into the Goombas.

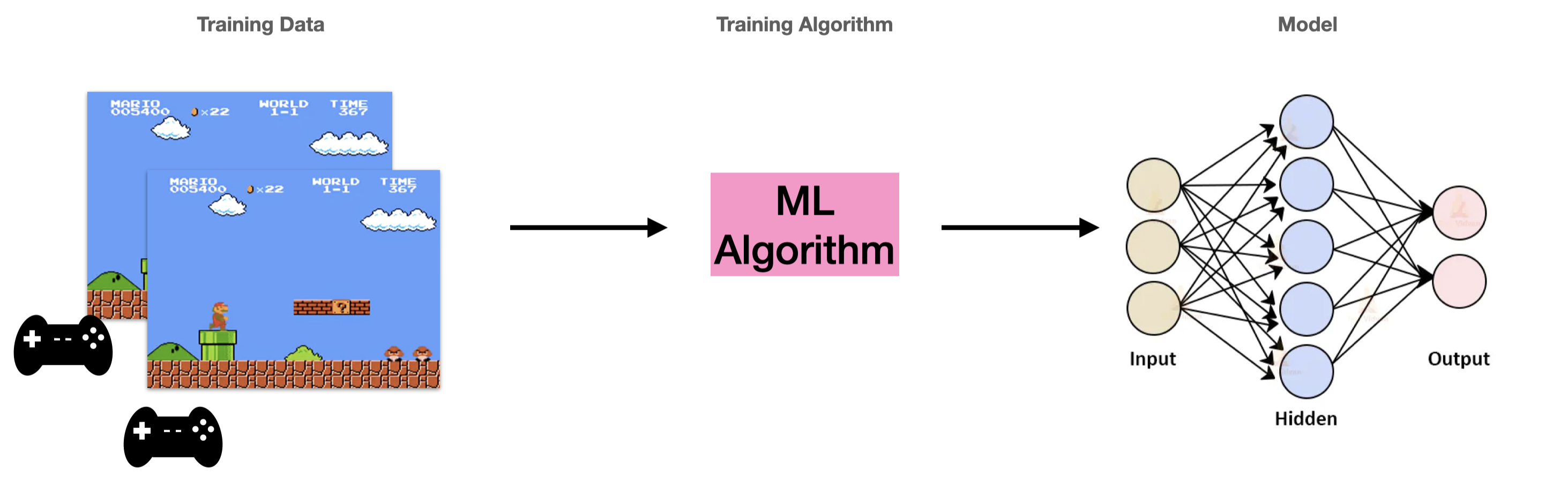

From human demonstrations, we can train a machine learning model to play Super Mario Bros:

In all, machine learning gives the computer the ability to learn like a human.

Why is it so hot right now?

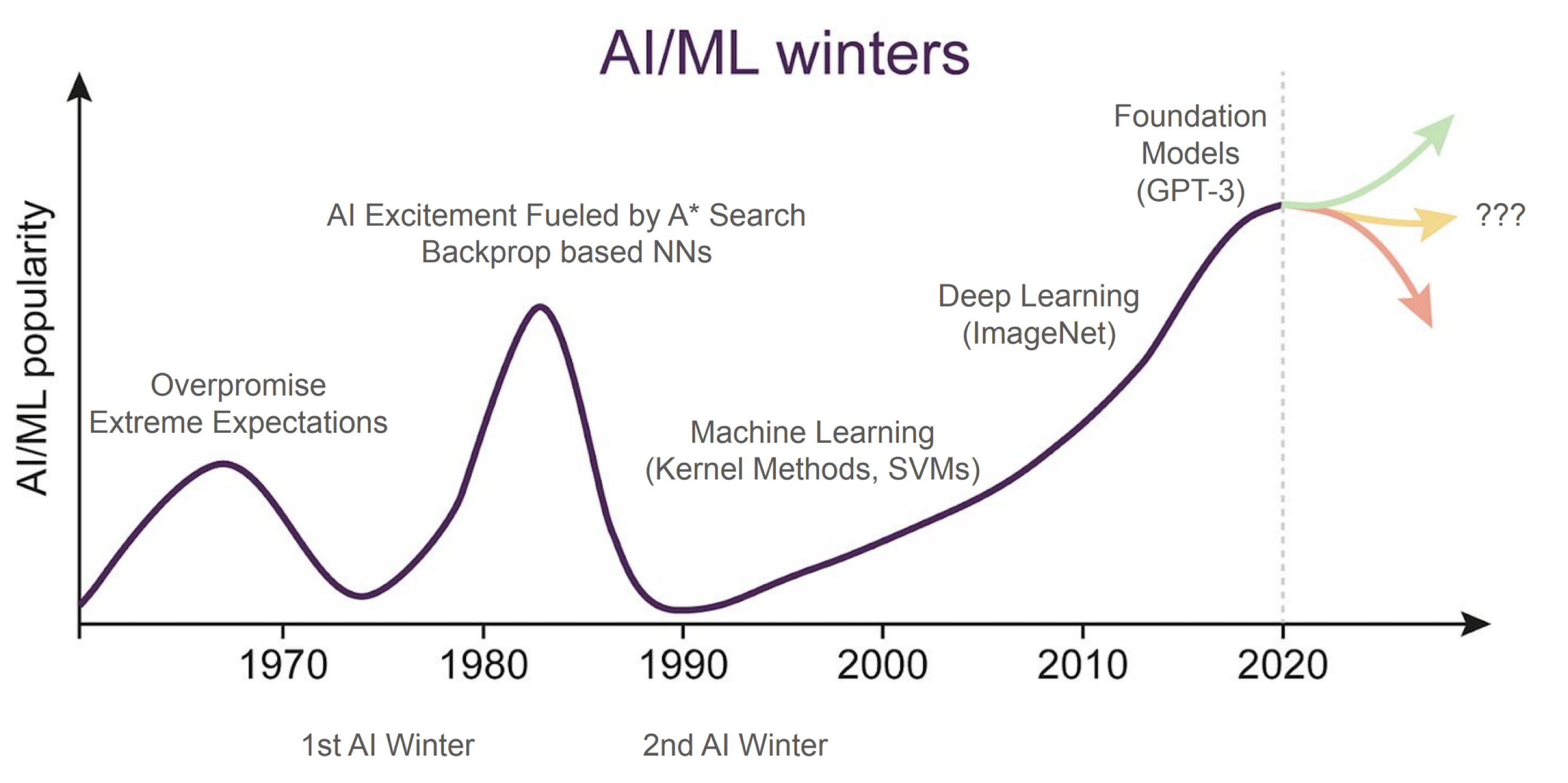

The popularity of machine learning has waxed and waned from the 1940s to early 2000s. It has regained popularity in academia in the last 13 years, and popularity with the public in the last 2 years.

Beginning around 2010, we started building machine learning-based models that were deeper and bigger. In 2012, performance in the ImageNet competition shot up and surpassed the threshold of what researchers thought was possible for any computer program. Researchers started to get excited about the capabilities of deep learning.

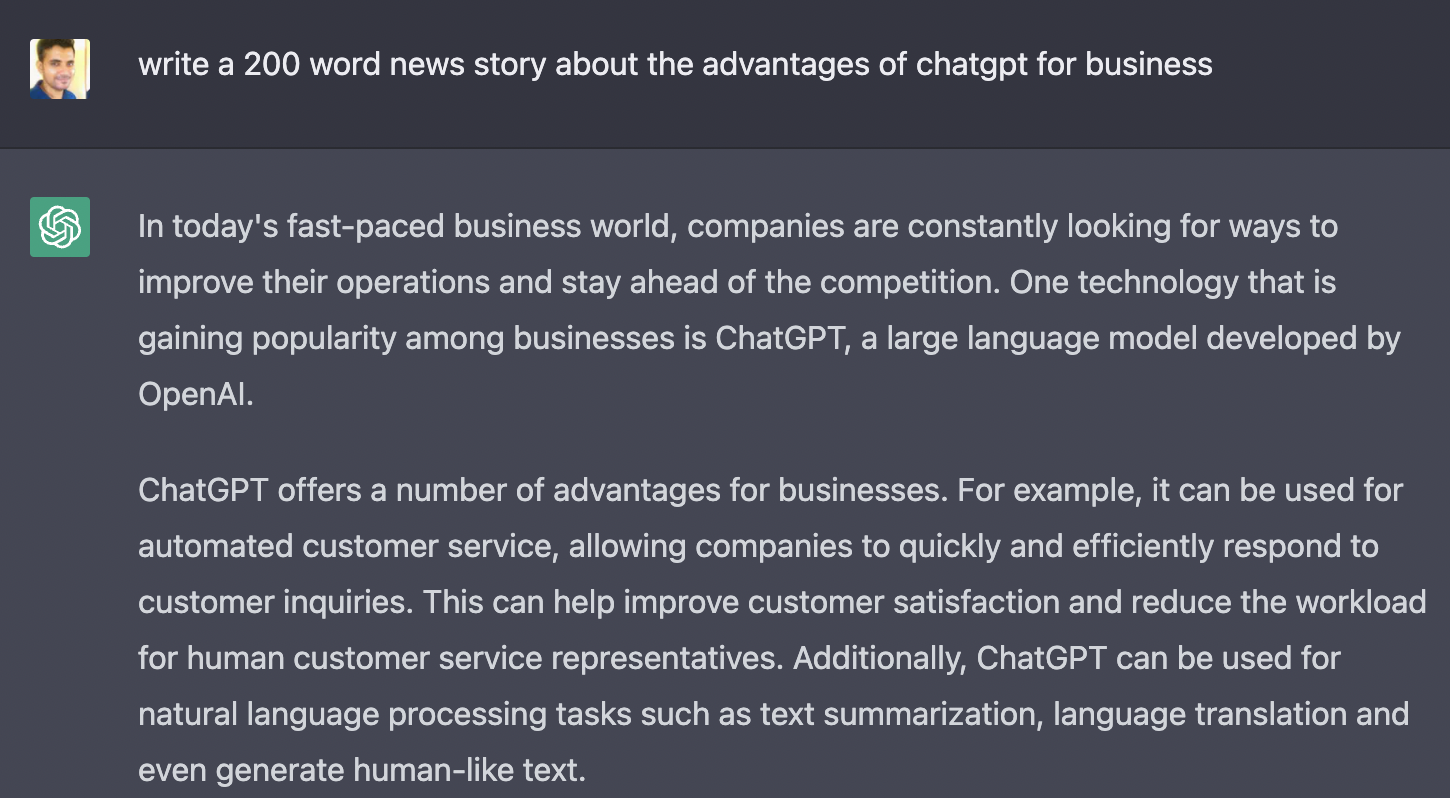

In 2016, Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol, one of the best players in Go in a match, and it was not a close match. In 2022, OpenAI launches ChatGPT, a Large-Language Model (LLM) that processes almost every natural language query. ChatGPT gained over 100 million users in 2 months. See below for an example. Following closely are rivals like Gemini, LLaMA, Claude, and recently DeepSeek.

How have machine learning-based algorithms become so good? You might have heard that these models are getting bigger, trained on more data, and require substantial resources.

The xkcd comic above shows a common misconception that machine learning is all about throwing the latest resources together and seeing if it works. Some part of that is true, but the connotation is that machine learning scientists are blind monkeys at work. I want to break this assumption and introduce a principled way we can reason about machine learning.

What makes a good machine learning algorithm?

Recall the setting of training a model to play Super Mario Bros. We may have a series of human demonstrations and train a model to replicate that behavior.

How can we measure the success of the algorithm? When we let the trained model play the game, we want the computer to complete the levels, avoid death, keep moving to the right, and collect coins and power-ups.

In machine learning, we typically consider how terribly the model performs in the real world, and we call that the true error. So the goal of machine learning is to produce a model that minimizes the true error.

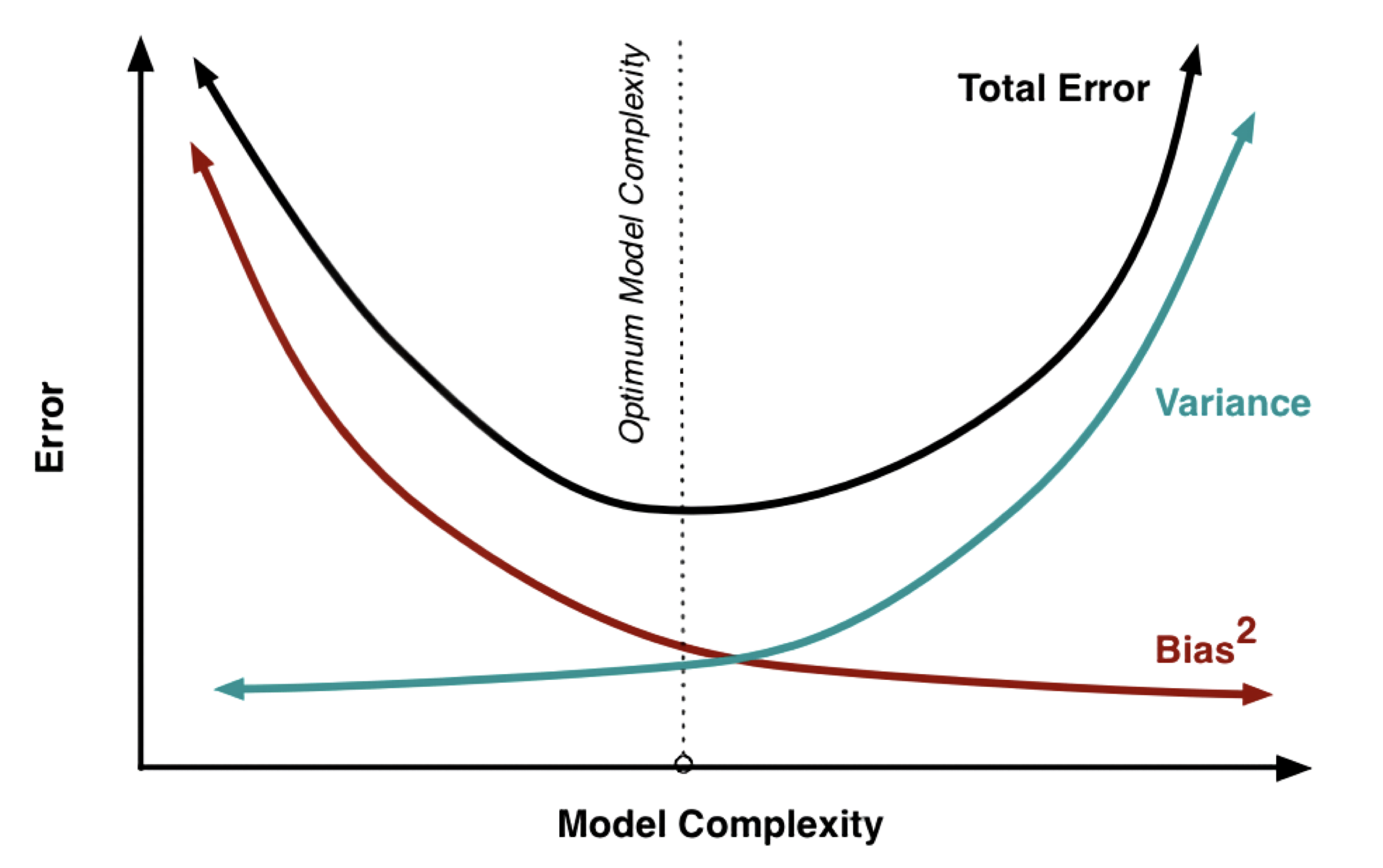

We will now introduce the key principle for reasoning about machine, the bias-variance decomposition:

\[\textsf{true error} = \mathsf{bias} + \mathsf{variance}\]Bias is the absolute best error we can achieve when our machine learning algorithm is given unlimited data, memory, and compute. In the real world, it’s not possible to have unlimited data, memory, and compute. So variance is the variation you usually have from the best error due to the limited data, memory, and compute. Typically, bias and variance have a tradeoff: as you increase one you decrease the other.

Interpret the diagram above where the \(x\)-axis is the model complexity and the \(y\)-axis is the true error (called total error here). As model complexity increases, the bias decreases because that complex model can learn how to solve difficult tasks given enough data, memory, and compute. However, variance increases because it’s hard to find the exact optimal model when it is so complex. This is called overfitting.

As model complexity decreases, the bias increases because the model is not powerful enough to solve a difficult task. However, variance decreases because the model is smaller and easier to train to find the optimal model. This is called underfitting.

ChatGPT: A Case Study

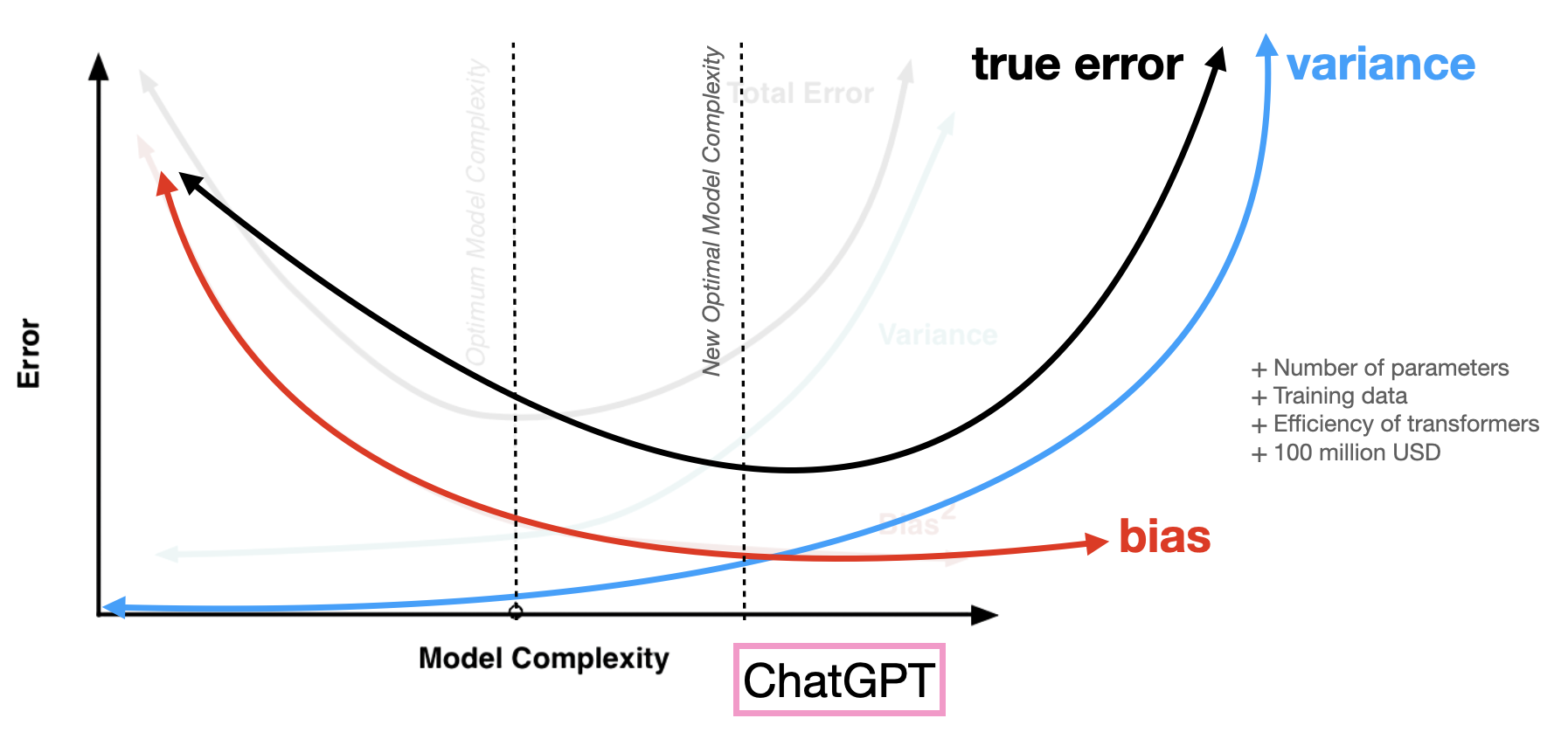

Why is ChatGPT such a good chat bot? In the 1990s we were studying neural networks with a few hundred parameters, and in the 2010s with a few million parameters. GPT-4 has around 1 trillion parameters. This suggests it has low bias—but doesn’t that mean higher true error due to variance?

The trick is that we can lower the variance curve. First, ChatGPT is trained on a lot of data, essentially on text across the entire internet. This alleviates the data bottleneck in the variance. Further, ChatGPT takes advantage of a transformer-based architecture that is very efficient when used with Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and GPT-4 trained over several months, costing over 100 million U.S. dollars. This alleviates the compute and memory-bottleneck in the variance. Thus ChatGPT pushes the variance curve down to look like this:

Why did OpenAI spend millions of dollars training its LLMs? Because they knew it would work. They found reliable scaling laws that showed a predictable decrease in true error given that model size, data, and compute power all increase.

Will AI take over the world?

When I was first introduced to machine learning, I thought machine learning would be the answer to life, the universe, and everything. Maybe, just maybe, we could develop a superhuman general intelligence that can solve all of our problems.

We have learned about how the bias-variance decomposition guides machine learning scientists to make better machine learning algorithms. However, there is a limit. Machine learning is nowhere close to general intelligence.

Machine learning can make mistakes. Self-driving cars can misidentify telephone poles and crash into them. Even ChatGPT can make mistakes, called hallucinations. ChatGPT can’t find citations for you. ChatGPT can’t draw a glass half-full of wine.

Machine learning is biased if the data is biased. Google search results for “unprofessional haircuts” have returned a disproportionate amount of black women with natural haircuts. Google’s Gemini tried to unbias its image generation which lead to unprompted generation of historically inaccurate figures like a Black pope or an Asian Nazi.

Machine learning can be used maliciously. Deepfakes of political opponents during campaigns spread misinformation. Recently, millions of users have used ChatGPT to turn their photos to mimic Studio Ghibli’s style. In 2016, Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki said himself that AI generated art is “an insult to life itself”. Finally, machine learning-based recommendation systems for YouTube, TikTok, X, and the like recommend videos that keep us on the platform, that provoke us to stay on that platform out of fear, anxiety, or to get that sweet rush of dopamine.

Summary

Machine learning gives the computer the ability to learn like a human, from experience, past and present, and genetic (built into the model). Thanks to the bias-variance decomposition, we have been able to reason about machine learning. With the benefit of complex models, efficient computing, and more data, machine learning algorithms have surpassed all expectations from games to chat bots to image generation. Yet, it’s important to note that they are not general intelligence, they only do what the data says, and what we design it to do.

Acknowledgements: Adapted from Fall 2023 CS 4780 when it was taught by Wen Sun.

- CS 4780 Introduction to Machine Learning @ Cornell

- CS 4782 Introduction to Deep Learning @ Cornell

- You are a better writer than AI. (Yes, you.) by josh (with parentheses)

- Why Can’t ChatGPT Draw a Full Glass of Wine? by Alex O’Connor

- The Bias-Variance Tradeoff by Jared Wilber & Brent Werness

- Spring 2025 Splash @ Cornell Slides